Personal notes on social media outrage

My new year’s resolution is to engage with social media in a different way. What follows is an incomplete tour of some scholarship on social media outrage, along with speculative notes that are personal in nature. The goal of this reflection is not to solve any particular problem, or to advance any particular argument, but simply to make peace with the gap between what I want social media to be and what it actually is.

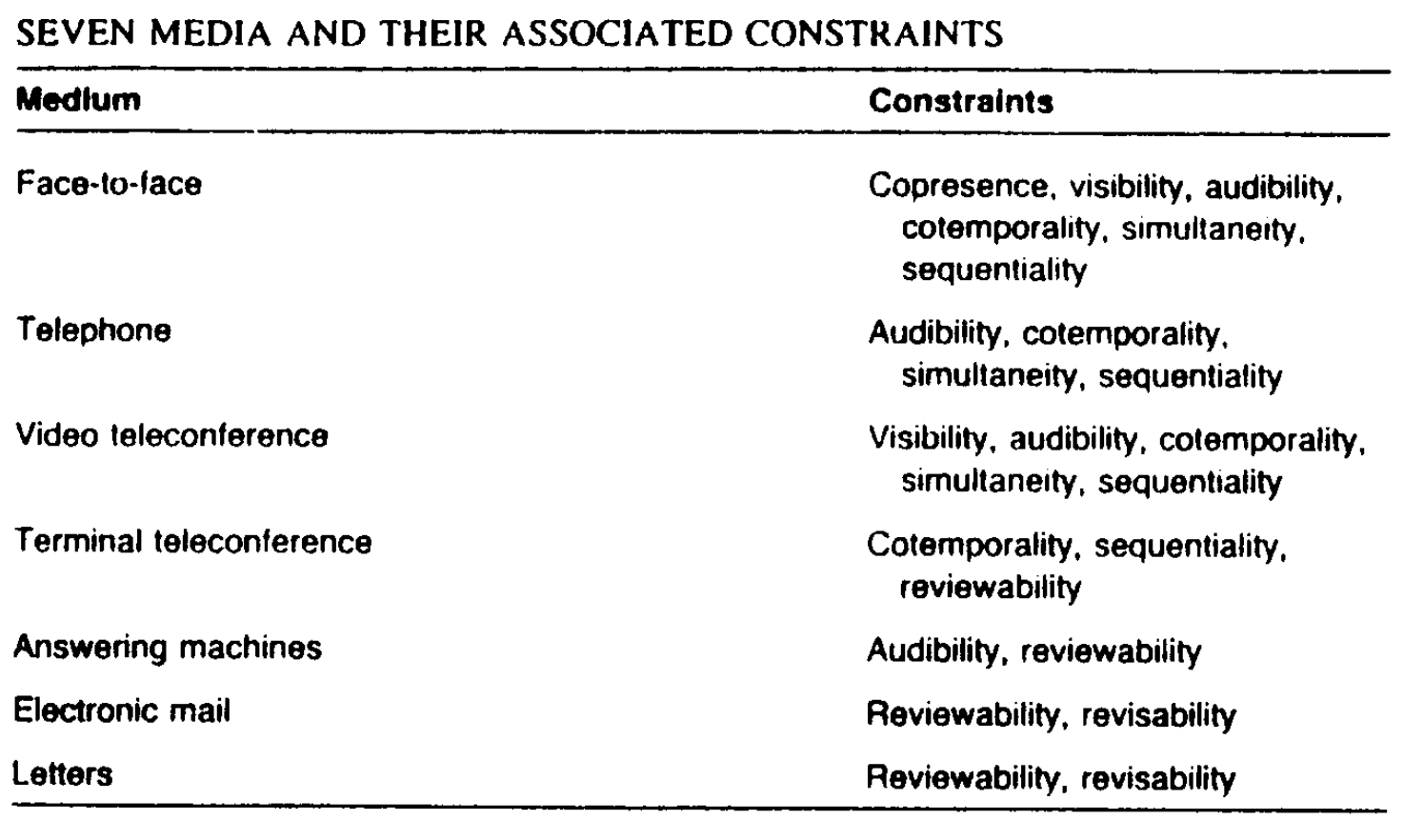

Everyone I know has had at least one terrible experience with outrage on social media, and everyone I know feels these conflicts were made worse by technological constraints. Online, much of what we use to make sense of another’s meaning is simply missing: no facial expressions, no tone of voice, no rhythm, no speeding up or slowing down, no laughter, no movement. Communication is atomized into individual posts, where the only context is a postage-stamp-sized profile photo and, if you’re lucky, a brief bio. “Postdoctoral researcher in Psychology at Harvard University." An opinion, a marker of social status, and the barest trace of a social relation (“follower,” “friend”). This is a familiar frame, beautifully introduced in the early 1990s by Herbert Clark and Susan Brennan, who outlined how constraints like these impose hard cost tradeoffs on conversation partners.

Do these constraints and their attendant costs account for widespread social media outrage? I think they can’t possibly tell the whole story. After all, despite its disembodied, inhuman character, conversations on social media usually go reasonably well. A tremendous number of people (billions!) use social media to stay in touch with friends and family, to share work with their professional communities, to gossip by the virtual water cooler, and so on. Despite the technological constraints, we make do. We adapt. So what accounts for the rage?

One popular explanation is that people (in cahoots with automatic recommendation systems) curate their online experiences to avoid ideas they find uncomfortable, creating an “echo chamber” or “filter bubble” that insulates them from opposing viewpoints, allowing them to achieve a kind of blissful but politically dangerous epistemic closure. Outrage ensues when the bubble pops. This explanation was in vogue around the election of Donald Trump to the US presidency in 2016. I was captivated by the problem (and discourse about the problem), and wrote a post reviewing a large study on filter bubbles and another post on search engines, social media, and online echo chambers. Here, I’ll be brief: echo chambers and filter bubbles probably do not explain the mess we’re in. Far from living in epistemic isolation, people online are exposed to more cross-cutting opinions and beliefs than ever. Dealing with these cross-cutting opinions turns out to be hard.

The outrage machine

One way cross-cutting opinions are hard is that they make us angry. And work by William Brady has shown that people are more likely to share posts that are morally and emotionally charged. Sharing makes us angry, and being angry makes us share. This feedback loop is comically tight.

It’s tempting to stop here. Coupling the vast scale of social media use to the moral-emotional outrage engine seems more than sufficient to account for widespread conflict, public shaming, harassment, and so on. But moral emotions do not begin and end with posting, and being online is not the alpha and the omega of social engagement. Sometimes (sometimes!) feelings drive us to act, and understanding outrage on social media requires taking a close look at these actions and their consequences. We should be open to the possibility that outrage is… good, actually?

In The Upside of Outrage, Victoria Spring, C. Daryl Cameron, and Mina Cikara argue that outrage often produces desirable outcomes, like donations to political causes, participation in protests, support for political candidates, and so on. This resonates with me; I have been deeply affected by the social media sharing of video evidence showing widespread abuse of police power in the United States. Earlier this year, my outrage drove me to reevaluate police abolition—I used to think the concept was unrealistic, but now it seems crystal clear that the problems in police culture are deep enough to resist comparatively minor reforms. This change of heart has given way to changes in action: I’ve made a habit of donating to organizations that work on US criminal justice reform. Following this line of thought, it’s obvious that avoiding outrage has profound costs. A US resident in retreat from social media outrage in 2020 could not appreciate the full force of an emerging social movement. They would be missing out.

Despite being convinced that outrage has upsides, I don’t think we should be convinced that we live in the best of all possible social media worlds. In their response piece, How Effective is Online Outrage?, William Brady and Molly Crockett point out that having upsides in some important cases doesn’t necessarily mean outrage is good overall. Worryingly, the architectural constraints imposed by social media might make the negative effects of outrage more likely—in particular, the authors note that harassment targeting minorities disincentivizes their participation in public life, and that this lack of representation may have a wide variety of negative knock-on effects.

Cui bono?

We’re left with an important, unanswered question: Who benefits from social media outrage? It’s not clear, but I think there’s reason for pessimism.

First, I suspect it’s easy to fool oneself into believing that the benefits of social media outrage go to the morally righteous, while the costs accrue to the unjust. This is simply not the case. More often than anyone would like, both sides of a social media conflict turn a profit. It’s easy to feel good while watching the likes, faves, and retweets roll in on a solid dunk, but it’s naïve to think one’s ideological opponents aren’t getting exactly the same benefits from their counter-dunks. One somewhat brutal way to appreciate this is to follow police officers that are placed on administrative leave after public outrage over their actions—their communities rally to support them, often via direct financial contributions on sites like GoFundMe or GiveSendGo.

This is related to a larger problem about how the effects of social media outrage ripple out into the larger political ecosystem. The current strategy of the Republican party seems to be to provoke as much reactance as possible—“Don’t tell me what to believe!"—appealing to petty grievances to drive the middle class to the right. Disturbingly, this strategy leaves nothing off-limits. Even mask wearing during a pandemic has been made a partisan political issue. This scorched-earth approach is not new, and I remember hearing debates about “political correctness” on talk radio in elementary school that feel eerily contemporary in their dishonesty. But it would be a mistake to think that social media platforms are blameless cogs in a pre-existing political machine. Sure, we might be having similar fights without social media, but the unprecedented scale of social interconnection on the internet changes the stakes. Just as television bears some responsibility for the Satanic Panic and false charges of child abuse in the 80s, social media platforms arguably ought to bear some responsibility for the violence of QAnon, the genocide in Myanmar, the spread of vaccine misinformation, and so on. How this responsibility should play out is a complicated question, which I’ll set aside for now. My focus here is more personal: When I get into an outrage-driven conflict, even when it feels like I’m “winning,” I can’t shake the worry that these distant, hard-to-quantify systemic costs accumulate faster than the benefits.

It’s also clear that the most immediate beneficiaries of social media outrage are the social media platforms themselves. It’s common practice for platforms to “optimize for engagement,” iteratively changing how a platform works to increase the amount of time people spend on it. (The US Senate Committee on Commerce, Science, & Transportation held a hearing on optimizing for engagement that makes for interesting reading.) This might sound benign, but the most engaging content is often outrageously offensive, outrageously false, or both. As pointed out by Wael Ghonim and Jake Rashbass in Transparency: What’s Gone Wrong with Social Media and What Can We Do About It?, this incentivizes social media platforms to spread outraging material widely, insofar as it increases users' time on site. Combined with automatic recommendation systems and other ethically dubious strategies for increasing engagement, social media platforms have come to resemble addictive slot machines that sometimes show you a cute cat photo, and sometimes scream at you like a drunk looking for a fight. As bad as this is, we keep scrolling and clicking.

Bad behavior

Finally, I think many outrage-driven social media dynamics are simply unhealthy in and of themselves. Some of these are obvious, like piling on and harassment. I’m happy to assume the costs of these bad behaviors outweigh the benefits. The behaviors I describe below are less obvious, and probably not unique to social media (though I suspect the context-collapsing constraints of social media make them worse).

It’s common practice, though wanly frowned upon, to take advantage of outrage-driven sharing by generating “clickbait” versions of ideas. Clickbait captures enough of the spirit of the original idea to maintain some level of persuasive power (and plausible deniability), but its ultimate goal is to grab attention at any cost. This gives rise to “second-order clickbait outrage,” where attempts to disambiguate the original claim from its mutated clickbait cousin are mistaken as a defense of or attack on the clickbait claim itself. For example, the term “emotional labor” has a deep history in sociological and political thought, capturing how participation in the labor market imposes severe (and frequently gendered) demands on how workers manage their emotions. Erica West in Jacobin traces the clickbait-ification of “emotional labor," showing how social media outrage collapsed the concept into a perversely neo-liberal dunking tool, delivered in the form of a faux “emotional labor invoice." Because outrageous internet dunks are more sharable than decades-old articles on sociological theory (and may even be more effective at changing hearts and minds!), the concept of “emotional labor” simply is a clickbait dunk for most people. To them, defenders of the deeper meaning of “emotional labor” seem to be defending the dunk, making it difficult to have a meaningful conversation, and producing another opportunity for outrage-driven conflict.

Another feature that seems to drive social media outrage is disputability. Disputable outrage spreads more readily than obvious, indisputable outrage because social conflict motivates sharing. (I believe I first encountered this idea in a now-deleted Twitter thread by Adam Elkus.) If one group can look at a news story and see it as outrageous, while another group that makes slightly different, disputable assumptions can look at it and see it as normal, then both groups are in for a bad day on Twitter. Each group will use either condemnation or defense of the news story not only to engage in public debate with out-group members, but also to test the loyalty of other in-group members. The threat of ostracism makes it costly to go against the grain. I should note that shared outrage does have valid affiliative uses! It can sometimes be healthy to demand that people close to you to share your anger. But this dynamic can become deeply pathological, especially when the outrage is driven by clickbait mutations of complex ideas. In these cases, people will devote endless energy to attacking or defending weak, sometimes nonsensical clickbait as a way to broadcast their social affiliation and test others close to them. Distressingly, the more absurdity one is willing to risk for one’s cause, the deeper one’s affiliation appears to be.

Happy new year

So here are my commitments for the new year.

- Focus on durable intellectual work.

- Disengage from the major social media platforms. Instead, relate to people directly or on alternative platforms at a small scale.

- Be circumspect about the unpredictable costs and benefits of trying to change others' minds.

- Channel outrage toward support for organizations with practical and effective solutions.

- Focus on the strongest version of each idea, ignoring clickbait discourse.